Testing is at the core of all complex software systems that exhibit any sense of quality - and works well for developers sanity. It's the main tool that helps us convince ourselves that what we created will probably work correctly before actually running it in production.

There are tons and tons of books and information out there about software testing, this falls into a slightly more specific niche that is back-end services testing, potentially in a distributed environment. It's unlikely to be of much use for GUIs, desktop software, safety critical systems, developer tools nor very large monoliths (browsers, operating systems). This can also be highly product and domain-specific.

This is also not going to be about the old-fashioned way of testing - manual testing, separate automated QA via selenium etc. This is about developers owning their work and striving for quality. Though on the other spectrum - this is going to be mostly about pre-production verification and its impact on future changes. This is also not going to touch continuous integration, continuous deployments, prod-pars, observability, different types of deployments and many other quality assurance techniques, although these are a vital part of a well-oiled system too.

Preface

There is no silver bullet, no single proven solution emerged so far, additionally available tools and techniques used in creating good tests is a continuously expanding domain (albeit rather slowly). A few years ago we didn't have docker, we didn't have testcontainers, there were no good embedded solutions. We had far weaker developer machines, fewer resources at our disposal and many approaches were too time-consuming to be viable (and they are still quite a challenge for big systems).

Treat this more like a guide than a set of concrete rules, your system might be different in ways that make it hard or even impossible to test efficiently in this manner. Ensuring high quality of software is a constant battle between available resources, execution time and complexity. While execution time and complexity are relatively within our reach having limited budget and time might be a showstopper. We might not be able to create multiple prod-like environments simply due to sheer costs associated with it, especially when we rely on multiple cloud services - queues, databases, warehouses, storages, 3rd party services, mainframes or even custom hardware. We might have to accept some trade-offs despite our best efforts. What's more, these costs usually don't grow linearly, getting basic testing in place is relatively cheap and gets us very far but getting a few prod-par environments and vast end-to-end tests can easily multiply our costs.

Tests are 'a best effort' verification of the system

This is shown from an engineering perspective, unlike in mathematics, it's about handling the trade-offs and balancing risks - given requirements we are attempting to reasonably get there, not necessarily always proving it.

Terminology

I don't think the typical test divide is of much use, everyone has their own understanding of what a 'unit' or 'integration' should mean - and it probably varies from context to context too. What I could endorse is dividing tests into two categories, mostly for convenience:

- Functional tests check for functional correctness and usually answer very specific, domain oriented questions like:

- Will this request create a new user?

- Will this payment be registered and funds transferred? Will it also notify a 3rd party service?

- Will this request create a new virtual machine?

- Will this request find all user files?

Such tests are commonly known as end to end / integration tests.

This kind of testing makes it harder to instantly know WHY something doesn't work, that's fine, what is crucial is to know that something is broken and we don't get false positives, even if finding the root cause takes a few moments it's fine.

- Technical tests - sometimes it's useful to make sure that technical constraints are also met:

- Do we correctly clean old data from this collection? Do we keep memory under given threshold?

- Are we processing a given request within acceptable time?

- Can we correctly fail-over to the secondary host? Will it preserve data?

- Are we getting to correct state after incidents or system specific events? Are we sharding correctly?

- Systems testing would fall under this category e.g., Jepsen testing

Depending on technical challenges there may be very few or even no technical tests, it might turn out that having good observability can be enough. Note, that in a service based architecture functional tests may be served by a single service (probably most of them), or they might require half the system to be up and running, including databases and middleware.

To be honest, in the end this kind of tests can also easily fall under functional category, after all ability to retain data by a database is its key functionality.

It's useful to additionally divide tests by their running time, having two tags slow/fast is generally sufficient. This makes it easy to frequently run 'fast' tests during development and only rarely execute fully fledged slow, E2E tests.

What, why, how

There is only one, singular primary goal for testing - to ensure correctness and quality, to achieve that the only way is to create simulations that can reliably imitate production environment. No rules will help us improve this part, it seems to boil down to engineer individual traits and experience. We can improve our chances by creating a process that might be conducive to quality (e.g. mandatory reviews) but in the end what matters is our (and reviewers) perception, experience and thoroughness with a pinch of paranoia. I believe this to be especially true for new functionality.

Secondary goals are vital to keeping the system alive, open to change yet resistant to regressions. Tests should verify correctness for all critical functionality and at the same time they shouldn't block us from making changes to existing code. That is why old-fashioned testing where every single function is white-box tested is atrocious, add to that plenty of mocking style testing (like checking if a given method was called X times) and we get a perfect recipe for codebase that will never evolve. What we really need is fearless code modifications else we end up with a brand-new legacy system.

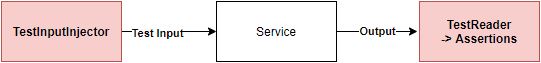

That's why the vast majority of our tests should be black-box functional tests of the API itself. What we want to know is that for a given inputs we get desired outputs or/and side effects, the fact that our system internally uses hashmaps, linked lists, 17 functions spread throughout 10 classes and stores data as a JSON blob should be of no interest to us!

What we actually should do is to invoke the API itself with real, preferably resembling production data and see if the output matches our expectations:

The inputs and outputs can be really anything, for example if the API is REST based then it's best to fire real HTTP requests and validate HTTP responses. The service in the diagram above can be anything really e.g. a calculator - we provide multiple important inputs "2+2", "7*12", "12/0" and only validate outputs -> "HTTP 200: 4", "HTTP 200: 84", "HTTP 422: Division by 0".

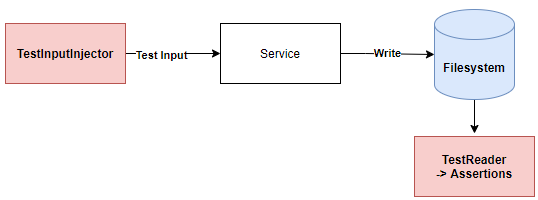

The time when implementation details might be important is when we need to validate side effects because we consider them the end-goal in itself - was an email sent? Was data written to disk? Sometimes it's possible to side-step it but definitely not always, or at least it's not always the reasonable approach.

There are only two main reasons when functional tests should be modified, when API itself changes or when the existing functionality changes - though if we expect the change to be backwards compatible it's probably better to write additional tests instead of modifying existing ones.

Changing the API should be rare in practice when the project is out of infancy, and even then we might need to keep the old one alive in order to serve legacy clients.

Tests must be consistent and reliable. Tests that intermittently fail are just an annoying hindrance, people sooner or later stop paying attention to them letting the rot begin. Consistency is usually achieved by not relying on external, shared state and by avoiding the usual code smells like not using runtime provided dates and system clock, not using non-deterministic algorithms (like iterating over maps) etc. There are many other, better sources that describe in detail how to create consistent and reliable tests.

External services, side effects and other building blocks

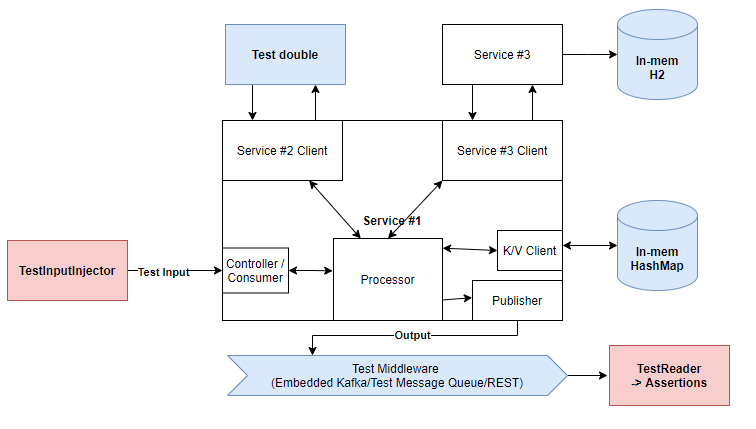

All the above works well and is quite easy to execute as long as our services don't require external services, or potentially persistent state to function, for example a database. In such cases it's useful to leverage embedded versions if possible (e.g. Kafka provides such Java implementations) or slightly different, but mostly conforming (e.g. H2 in-mem database in tests in place of PostgreSQL that is used in production). If there are no such solutions, it might be worthwhile to create a test double (e.g. key-value store implemented as a hashmap).

Most tests will work within a single service scope (and its direct dependencies, like middleware, databases etc.) resembling the following:

The filesystem in this diagram can be any side effect, in this case we can assume that one of expected functionalities under test is to write some transformed data to a filesystem in some specific format. We make API calls and can create assertions directly on the filesystem itself leveraging our test infrastructure. How it's done internally by the service is inconsequential for correctness tests.

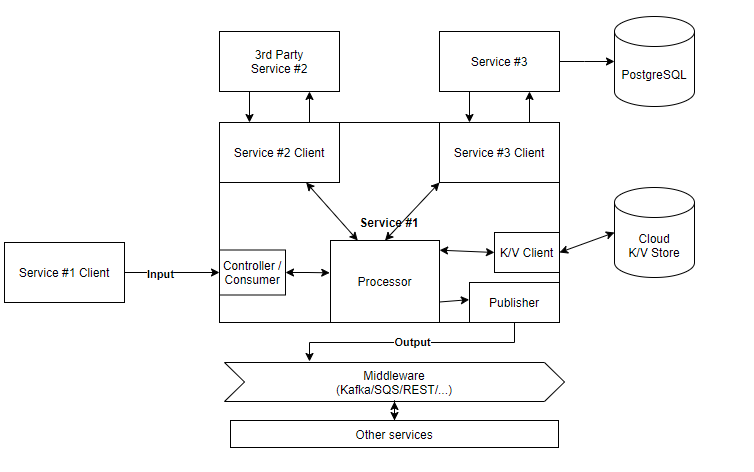

More complex, multi-service example, production environment:

Potential solution when tests are run locally:

The system must be nimble enough to work well in testing environment, databases should be easily built from scratch from scripts, state resettable and test data readily available etc. It requires more up-front work but usually is worth it in the end.

The problem with this approach is that our embedded versions and in-memory test doubles might behave almost like real services - but almost is not always sufficient, and sometimes it's really hard to simulate required functionality (e.g. proprietary cloud solutions).

At this point it's getting costly, but to alleviate such problems we can model our infrastructure as a code - including testing environment. If done well it makes it relatively easy to run all tests locally with test doubles and potentially substitute them with real implementations in our CI pipelines.

With the rise of containerization, and Docker in particular, it's slowly getting easier to test locally with real components instead of their mocks/doubles, this can be facilitated e.g. by Testcontainers. Testcontainers integrate JUnit based tests with Docker containers running required infrastructure - this looks promising but unfortunately is not feasible for quick testing during development. The startup time is too slow to restart the state before each test and this is a problem that I don't think can be solved anytime soon. Alternatively we could run a single instance of each component and force developers to 'clean' the state after each test on their own - personally I haven't seen much success with this approach (yet).

The rule of a thumb is don't use mocks (too much) unless there is no other sensible way. Use embedded versions, test doubles, sometimes custom implementations. Nonetheless, there are very legitimate situations where mocks are needed/useful, a few examples:

- Simulating failures

- Caching: we need to verify that the cache was actually hit to retrieve data.

- Sending emails: technically we could set up a real email server and check it there, but it seems a little too excessive in my opinion.

- 3rd party services that are hard to emulate in a way that provides value (especially true in DevOps/Cloud environments)

- testing on real infrastructure, or writing good test doubles is not worth the effort

It's not enough to verify that a method on a mocked service was called, what we really want to know is if it worked - and in order to make sure that it worked we also must be sure that the expected contract with that service is fulfilled by both sides. Test environment should be a best effort simulation of production environment, the more we mock the more we lack in verisimilitude and loose confidence.

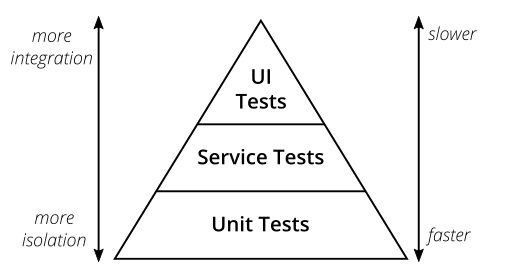

The testing pyramid

The most commonly met 'pyramid of automated testing' is probably the one done by Mike Cohn in Succeeding with Agile:

This approach might make a lot of sense when we think about convoluted monolith applications where the service/functional boundaries are hard to draw, or when pretty much everything is dependent on everything else.

Typical unit tests are quite useful either for more technical parts (checking if collections are empty, cleaned etc.), or places where running lots of functional tests is not feasible/too costly, i.e. when we want to run hundreds of tests to test e.g. validations.

Some people even suggest deleting such tests once verified, I'm not convinced about it, maybe we should just mark them with @Technical tag or something similar to let everyone know that this failing test doesn't necessarily indicate correctness problems and might be a natural consequence of code refactoring.

Developer workstation - suitable for running the system

There is a huge jump in productivity, communication overhead and simplicity once all tests can be run on a local machine. Such tests are trivially debuggable and usually don't require shared resources - or such resources are created from scratch on-demand. This is cost, time and communication-wise far more efficient to maintaining many shared environments. Not to mention all the problems that we get from such environments, especially when the team grows significantly.

If a system is so big that it can't really fit into a single machine, we can write E2E tests in a slightly more sophisticated way. It's rare that any given functionality or flow requires the whole system to be up and running, instead we can declare which services are required for a test and run only those. Obviously there is a theoretical limit, technically a system might be too big to fit into a single machine for testing purposes, that limit is quite far and only getting pushed further every single year.

For very, very large systems it might not be feasible to write a lot of system-wide functional tests, in such cases we'll most likely end up with most tests scope limited to a few/single service and only a handful of system-wide end to end tests (potentially executed on an external system, daily) - if we really deem them necessary.

If your company has enough resources (and is willing) to provide each developer with his own production-like environment on demand, then good for you.

TDD, regressions

Every single regression should be covered by a test, a test written before doing any fixes. Actually, regressions are the perfect place where TDD actually yields reasonable benefits.

Other than that and maybe maintenance type development TDD sounds like a huge pile of inefficiency, especially for newly written parts that aren't heavily coupled with existing codebase. Maybe I'm just not that great developer but implementing new software seems to be a continuous process interleaved with designing and coding. I start with rough drafts and ideas but by the end these tend to differ a lot from final implementation, even APIs evolve significantly in the process.

Caveats / Closing words

This is already too long, yet I feel like we only scratched the surface. My original idea was way too ambitious for a single blog post, I wanted to cover things like test elegance, coverage, formal methods, prod-pars, test DSLs, configuration setup and provide actual code samples, regrettably it turned out that almost each one could be a separate post on its own.

Lastly, you can't catch all bugs, quality assurance is getting unreasonably expensive very quickly for general purpose software. Sometimes it's just better to fail fast, eat the cost and move on.